Relative Entropy and its role as a cost function for machine learning tasks

Contents

- Introduction

- Relative Entropy

- Quantities derived from Relative Entropy

- Relative Entropy in Machine Learning

- References

Introduction

I had been seeing terms like entropy, cross-entropy, KL-Divergence, information gain, etc., regularly in association with cost functions in machine learning tasks. For example, cross-entropy loss is used as the cost function in multi-class classification problems; maximum entropy principle in Bayesian inference, etc. All these quantities seemed related and I decided to find the meaning and the origin of each of these terms. It turns out that all these quantities can be derived from the Relative Entropy which is synonymous to KL-Divergence.

This post, starts with the description of Relative Entropy and what it means when viewed from various perspectives (statistical, information theoretic, etc.). Then it goes on to derive some other related quantities like Entropy (Shannon’s Entropy), Cross Entropy, Conditional Relative Entropy, etc. Then the last section talks why and how we use Cross Entropy as a loss function in classification.

Relative Entropy

Firstly, it needs to be noted that Relative Entropy has various names which stem from its use in various fields of study. Following are all synonymous:

-

Relative Entropy

-

KL-Divergence

-

Information Gain

-

KL-Distance (its not a true metric)

-

Discrimination

Relative entropy of a probability distribution \(p(x)\) with respect to \(q(x)\), where \(p, q\) are defined on the same set \(X\) is defined as follows,

$$ D_{\mathrm {KL} }(P||Q)=\int _{X}\log {\frac {dP}{dQ}}\,dP $$

which for the case of continuous probability distributions over \(X\) becomes,

$$ D_{\mathrm {KL} }(p||q)=\int_{X} p(x)\log{\frac{p(x)}{q(x)}}\,dx $$

and for discrete distributions, the integration changes to sum,

$$ D_{\mathrm {KL} }(p||q)=\sum_{X} p(x)\log{\frac{p(x)}{q(x)}} $$

Another point to note here is that this quantity is always greater than or equal to zero. It is zero when \(p=q\). This result is called the Gibbs inequality. Now, let us understand the meaning of the quantity from different perspectives.

Statistical perspective

In the space (statistical manifold) of probability distributions (where each distributions is a point) defined over set of events \(X\), relative entropy is like distance between two distributions. It is not a true distance metric because it does not satisfy the requirements of a metric (like symmetry). Nevertheless, it is an asymmetric measure of how much a probability distribution diverges from another. Derivation of KL-divergence is beyond the scope of this post, however interested reader is encouraged to check Kullback’s book[1]. If one sees closely, \( D_{\mathrm {KL} }(p||q)\), is the expected value (expectation w.r.t \(p\)) of the random variable \(y=\log{\frac{p(x)}{q(x)}}\) which is a function of the random variable \(X\). \(y\) is nothing but the logarithmic difference of the probablilities of \(X=x\) given by two probability distributions, ie. \(p\) and \(q\). Hence, roughly speaking, Relative Entropy is the expected value (expectation w.r.t \(p\)) of the difference in the probalilities w.r.t \(p\) and \(q\) respectively, for random variable \(X\).

Information theoretic perspective

The general term entropy can be thought of as the degree of uncertainty about the value of a random variable: More the uncertainity about the value of a random variable, lesser informative is its probability distribution. The informativeness of a probalility density function is can be thought of as the amount of uncertainty (entropy) it can reduce by providing some knowldge about the uncertain event (value of the random variable). For example, if \(X\) is a discrete random variable which can take values from \(\{1, 2, 3\}\) with probabilities \(\{0, 1, 0\}\) then there is no uncertainty (entropy) in the value of \(X\). Instead, if the probablity distribution were to be \(\{1/3, 1/3, 1/3\}\) then all the three values are equally likely and the uncertainty about the value of \(X\) is maximum.

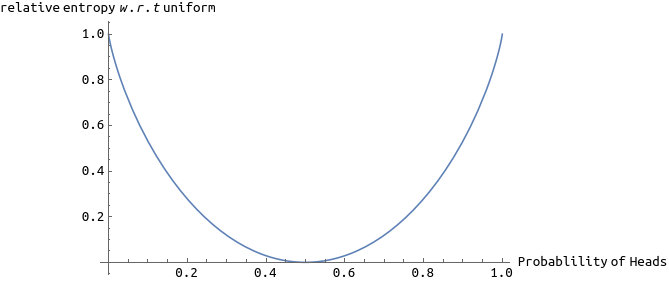

Hence, Relative Entropy can be thought of as the change (increase or decrease) in the uncertainty (information) about a random variable when moving to using a new probablity distribution \(p\) instead of old distribution \(q\). For instance, say we have a coin toss experiment and we assume that it is a fair coin, then the probablity distribution is given by \(q(H)=0.5, q(T)=0.5\). Now, someone comes and tells us that the coin was made defective and is biased towards heads with a probablility of \(0.8\) then our new probablity distribution would be \(p(H)=0.8, p(T)=0.2\) and the relative entropy of \(p\) w.r.t \(q\) will be \(0.8\log _2{1.6}+0.2\log _2{0.4} =0.27\). As the following plot shows, the relative entropy for new distribution w.r.t old (uniform) distribution reaches its maximum when there is no uncretainty.

Another good perspective to relative entropy can be from the coding theory. Assume that we have a bag full of balls of colors red, blue, green and orange. We are supposed to draw one ball with replacement and send the result (color of the ball) to our friend sitting faraway in the form of a message using a binary channel. First we need to choose an encoding for the colors and while doing so we wish to minimize the number of bits required per message on average. Let the probability distribution \(q\), for the colors showing up be,

$$ q(x) = \begin{cases} 0.4 & \text{,if $ x=$ red} \\\

0.4 & \text{,if $x=$ blue} \\\

0.1 & \text{,if $ x=$ green} \\\

0.1 & \text{,if $ x=$ orange} \end{cases} $$

Given this probability distribution, an optimal encoding would have different lengths for different colors with the length of the message for red being shorter than that of orange and so on.

Now supose we add a few more balls into the bag and the probablility distribution now changes to \(p\) as follows, $$ p(x) = \begin{cases} 0.1 & \text{,if $ x=$ red} \\\

0.05 & \text{,if $x=$ blue} \\\

0.8 & \text{,if $ x=$ green} \\\

0.05 & \text{,if $ x=$ orange} \end{cases} $$

If we still use the same encoding which was designed to be optimal for \(q\) then the expected length of a message would increase. Here, the relative entropy of \(p\) w.r.t \(q\), i.e. \(D_{\mathrm{KL} }(p||q)\) is the expected change in the length of a message due to the change in probability distribution.

Quantities derived from Relative Entropy

Shannon’s Entropy

Suppose we have a uniform probability distribution:

$$ q(x) = \begin{cases} 1/4 & \text{,if $ x=$ red} \\\

1/4 & \text{,if $x=$ blue} \\\

1/4 & \text{,if $ x=$ green} \\\

1/4 & \text{,if $ x=$ orange} \end{cases} $$

If we have another distribution \( p \) (which is different from \(q\)) for the same random variable \(X\), then Relative Entropy of \( p \) w.r.t \( q \) would be:

$$ \begin{eqnarray} D_{\mathrm{KL} }(p||q)&=&\sum_{X} p(x)\log{\frac{p(x)}{q(x)}} \\

&=& \sum_{X} p(x)\log{\frac{p(x)}{1/4}} \\

&=&\sum_{X} \left( p(x)\log{p(x)}-\log{1/4} \right) \\

&=& \mathrm{constant}-\sum_{X} p(x)\log{\frac{1}{p(x)}} \\

&\geq& 0 ~~\text{(using Gibbs’ inequality for relative entropy)} \end{eqnarray} $$

Hence, we can say that according to KL-Distance (relative entropy), the distribution \( p \) departs from uniform distribution by \( \sum_{X} p(x)\log{\frac{1}{p(x)}} \) amount. This quantity is denoted as \(H(p)\) and is called Shannon Entropy of probability distribution \( p \). Also, as a consequence of Gibbs’ inequality, it can be seen that the Shannon Entropy of Uniform Distribution is highest amongst all the possible distributions for a random variable.

Shannon’s Entropy – sometimes referred to as Entropy of a probability distribution – can be seen from another perspective. It gives the minimum expected bits required to encode (on a binary channel) an event taken from an event space with probability distribution \(p\). Here, we say “minimum” because the encoding is optimized for \(p\), i.e., events with higher probability have less number of bits in their encoding and vise versa.

$$ H(p) = E_p\left[\log{\frac{1}{p(X)}} \right] $$

Cross Entropy

From information theory perspective, we have seen that

-

Relative Entropy \( D_{\mathrm{KL} }(p||q) \) is the difference/change in the expected length of a message when we change the probablity distribution from \( q \) to \( p \) with encoding optimal for \( q \)

-

Entropy \( H(p) \) is the expected length of message when the probablity distribution is \( p \) and the encoding is optimal for \( p \)

Then what would be the expected length of a message when the probablity distribution is \( p \) but the encoding is optimal for \( q \)?

$$ \begin{eqnarray} C(p,q) &=& E_p\left[\log{\frac{1}{q}} \right] \\

&=& \sum_X p(x) \log{\frac{1}{q(x)}} \\

&=& \sum_X p(x)\left( \log{\frac{p(x)}{q(x)}} - \log{p(x)} \right) \\

&=& D_{\mathrm{KL} }(p||q) + H(p) \end{eqnarray} $$

Cross Entropy of \( p \) w.r.t \( q \) is denoted by \( C(p,q) \) and is defined as the expected length of a message when the probability distribution is \( p \) but the encoding is optimal for \( q \).

Conditional Entropy

From here on, let \( X \) be a random variable on event space \( A \) with probablity distribution \( p \) and \( Y \) be a random variable on event space \( B \) with probablity distribution \( q \). Also, lets denote \( H(p,q) \) as \( H(X,Y) \). Then

$$ \begin{eqnarray} H(X, Y) &=& \sum_{x,y \in A} P_{XY}(x, y)\log{\left( \frac{1}{P_{XY}(x,y)} \right)} \\

&=& \sum_{x,y \in A} \frac{P_{XY}(x, y)}{P_X(x)} P_X(x) \log{\left( \frac{P_X(x)}{P_X(x)P_{XY}(x,y)} \right)} \\

&=& \sum_{x,y \in A} P_{Y|X}(x,y) P_X(x) \log{\left( \frac{1}{P_X(x)P_{Y|X}(x,y)} \right)} \\

&=& \sum_{x \in A} P_X(x) \sum_{y \in A} P_{Y|X}(x,y) \left( \log{\left( \frac{1}{P_{Y|X}(x,y)} \right)} + \log{\left( \frac{1}{P_X(x)} \right)} \right) \\

&=& \sum_{x \in A} P_X(x) \log{\left( \frac{1}{P_X(x)} \right)} \sum_{y \in A} P_{Y|X}(x,y) + \sum_{x \in A} P_X(x) \sum_{y \in A} P_{Y|X}(x,y) \log{\left( \frac{1}{P_{Y|X}(x,y)} \right)} \\

&=& H(X) + E_X \left[ H(Y|X=x)\right] \end{eqnarray} $$

Here, \( E_X \left[ H(Y|X=x)\right] \) denoted as \( H(Y|X)\) is the Conditional Entropy of \( Y \) given \( X \). It is the expected (expectation w.r.t \( X \)) entropy left in \( Y \) given \( X \).

Conditional Relative Entropy

As mentioned earlier, Relative Entropy is the expected value of the logarithmic difference in the probabilities with respect to two different probability distributions for a random variable. Just like expectation of any function of random variables, we can condition this expectation on another random variable and take outer expectation w.r.t to that variable. For instance, suppose we have three random variables, \( X, Y, Z \) where \(Y\) and \(Z\) are defined on same event space \(B\) and \(X\) is defined on \( A \). We also have probability distributions \( P_{Y|X}, P_{Z|X}, P_X \). Then the conditional relative entropy between \( P_{Y|X} \) and \( P_{Z|X} \) is:

$$ \begin{eqnarray} D_{\mathrm{KL} }\left( P_{Y|X} || P_{Z|X} | P_X \right) &=& E_X \left[ D_{\mathrm{KL} } \left( P_{Y|X} || P_{Z|X} \right) \right] \\

&=& \sum_{a \in A} P_X(a) \sum_{b \in B} P_{Y|X}(b) \log{\frac{P_{Y|X}(b)}{P_{Z|X}(b)}} \\

&=& \sum_{a \in A} \sum_{b \in B} P_X(a) P_{Y|X}(b) \log{\frac{P_{Y|X}(b) P_X{a}}{P_{Z|X}(b) P_X{a}}} \\

&=& \sum_{a \in A} \sum_{b \in B} P_{XY}(a, b) \log{\frac{P_{XY}(a, b)}{P_{XZ}(a, b)}} \\

&=& D_{\mathrm{KL} }\left( P_{XY} || P_{XZ} \right) \end{eqnarray} $$

Mutual Information

Just like correlation coefficient is a measure of linear relationship between two random variables, Mutual Information is the most general measure of relationship between two random variables. It is the KL-Distance between the joint distribution and the product of marginals.

$$ \begin{eqnarray} \mathrm{I}(X,Y) &=& D_{\mathrm{KL} }\left( P_{XY} || P_X P_Y \right) \\

&=& \sum_{x,y \in A} P_{XY}(x,y) \log{\frac{P_{XY}(x, y)}{P_X(x) P_Y(y)}} \\

&=& \sum_{x,y \in A} \frac{P_{XY}(x,y)}{P_X(x)} P_X(x) \log{\frac{P_{XY}(x, y)}{P_X(x) P_Y(y)}}\\

&=& \sum_{x \in A} P_X(x) \sum_{y \in A} P_{Y|X}(x, y) \log{\frac{P_{Y|X}(x,y)}{P_Y(y)}} \\

&=& D_{\mathrm{KL} }\left( P_{Y|X} || P_Y | P_X \right) \\

&=& D_{\mathrm{KL} }\left( P_{X|Y} || P_X | P_Y \right) \end{eqnarray} $$

$$ \begin{eqnarray} \mathrm{I}(X,Y) &=& D_{\mathrm{KL} }\left( P_{XY} || P_X P_Y \right) \\

&=& \sum_{x,y \in A} P_{XY}(x,y) \log{\frac{P_{XY}(x, y)}{P_X(x) P_Y(y)}} \\

&=& \sum_{x,y \in A} P_{XY}(x,y) \log{P_{XY}(x, y)} - \sum_{x,y \in A} P_{XY}(x,y) \log{P_{X}(x)} - \sum_{x,y \in A} P_{XY}(x,y) \log{P_{Y}(y)} \\

&=& - H(X,Y) + H(X) + H(Y) \\

&=& H(Y) - H(Y|X) \\

&=& H(X) - H(X|Y) \end{eqnarray} $$

As mentioned earlier Entropy is a measure of uninformativeness of a distribution. Hence the equations above qualitatively translate to the statement: Mutual Information is the uninformativeness in \( Y \) minus uninformativeness in \( Y \) given \( X \) and symmetrically other way round.

Relative Entropy in Machine Learning

In Machine Learning, we are often trying to find the best set of parameters (through optimization) for the probability distribution which best describes the observed data. Since, relative entropy behaves like a distance metric (again, it is not a true metric but is like a metric) in the space of probability distributions, it is a good candidate to be used as the loss function for this optimization. However, in order to use relative entropy as the loss function we require two distributions. They can be:

-

prior and posterior distributions, in that case we maximize the relative entropy,

-

or one of them can be a non-parametric (empirical) distribution obtained from observed data with the other being the parametric distribution whose parameters we are trying to find

The second case often arises in classification task and we will have a look at this in detail.

Multiclass classification

A typical multiclass classification problem can be described as follows:

-

The output \(y\) can take values from a set of \(k\) categories, say \( \{1, 2, … , k\}\)

-

The input is a vector \(x \in R^{r}\)

-

We have \(N\) samples in our dataset: \(\{(y^1, \mathbf{x}^1), (y^2, \mathbf{x}^2), …, (y^N, \mathbf{x}^N) \}\)

-

Given an input \(\mathbf{x}\) our model \(P(Y| X; \theta)\) outputs the probability distribution for \(y\) over the categories \( \{1, 2, … , k\}\). We pick the category with the highest probability as the predicted output. Here, \(P\) is the parametric probability distribution for the output \(Y\) given the input \(X\). Now, this function \(P\) can be modeled in any form: logistic regression, neutral network, etc. Whatever, the model be, it will have a set of parameters \(\mathbf{\theta}\) which we are interested in finding through optimization.

In order to use relative entropy as the loss function, we first construct a categorical distribution \(G_{Y|X=\mathbf{x}}\) for every sample \( (y^i, \mathbf{x}^i) \).

$$ G_{Y|X=\mathbf{x}^i}(y) = \left[y \equiv y^i \right] = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{,if } y = y^i \\\\ 0 & \text{otherwise}\end{cases} $$

It has to be noted that \( G\) is non-parametric and hence a constant w.r.t \( \theta \) consequently \( H(G) \) is also constant w.r.t \( \theta \). Hence \( \underset{\theta}\arg \min D_{\mathrm{KL}}\left(G_{Y|X=\mathbf{x}^i}(y)||P_{Y|X=\mathbf{x}^i}(y;\theta) \right) \) becomes \( \underset{\theta}\arg \min H\left(G_{Y|X=\mathbf{x}^i}(y), P_{Y|X=\mathbf{x}^i}(y;\theta)\right)\). So the loss function can be taken as the following:

$$ \begin{eqnarray} L(\theta) &=& \sum_{i=1}^{N} H(G_{Y|X=\mathbf{x}^i}(y), P_{Y|X=\mathbf{x}^i}(y;\theta)) \\

&=& \sum_{i=1}^{N} \sum_{j=1}^{k} G_{Y|X=\mathbf{x}^i}(j) \left[-\log{\left(P_{Y|X=\mathbf{x}^i}(j;\theta)\right)} \right] \\

&=& \sum_{i=1}^{N} \sum_{j=1}^{k} \left[j \equiv y^i \right] \left[-\log{\left(P_{Y|X=\mathbf{x}^i}(j;\theta)\right)} \right] \end{eqnarray} $$

You can take the two class classification problem and logistic regression model for \( P \) and substitute these into the loss function mentioned above. It will simplify to give the familiar negative log-likelyhood loss function of logistic regression.

References

[1] Kullback, S. (1959), Information Theory and Statistics, John Wiley & Sons. Republished by Dover Publications in 1968; reprinted in 1978: ISBN 0-8446-5625-9.

[2] Lecture on Relative Entropy by Sergio Verdu in NIPS 2009

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: