computing SWZ of parallel robot manipulators

work in computational kinematics of parallel robot manipulators

About the work

This work described here was done by Dhruvesh Patel at Robotics Lab, Department of Engineering Design, IIT Madras under Dr. Sandipan Bandyopadhyay as supervisor.

This page gives an introduction to the work. Interested reader is encouraged to check the complete report here as well as the published[10] paper here. Please contact me if you are interested in colaboration or would like to have the source code for this project.

Note: The source code is not yet public as the topic is under active research with several research papers under review.

Introduction

Overview

Computing the workspace of a robotic manipulator is useful in analysis of an existing manipulator as well as in designing a new manipulator iteratively (Kilaru et al. (2015)[1]). Also, the knowledge of singularity-free regions in the workspace and their topologies can be very useful in real-time path-planning. Once this information is obtained offline, for a particular design of the manipulator, the issue of checking paths for singularities can be completely omitted from the problem of path-planning, bringing down its complexity considerably.

A parallel manipulator can be thought of as a set of serial manipulators combined at the end effector, which also means that analyzing the workspace of a parallel manipulator is more complicated than that of a serial manipulator. Owing to the closed loops of links present in a parallel manipulator, its workspace is plagued by another type of singularity, called the gain-type singularity apart from the usual loss-type singularity inherited from the constituent serial chains, which complicates the problem. These singularities are also referred to as type-I and type-II singularities in Gosselin and Angeles (1990)[3]. In order to perform a realistic analysis of a manipulator design, the physical limitations such as link interference and joint limits have to be considered along with the kinematic singularities. Checking for link interference is in general computationally intensive, and the number of times it is performed should be kept to a minimum to restrict the total computation time within realistic limits.

Keeping all these issues in mind, this work presents and compares the performance of a set of algorithms to find the Safe Working Zone (referred to as SWZ hereafter) of parallel manipulators with two and three degrees-of-freedom. The algorithms presented in this work are implemented in C++ language.

Existing Literature

Avoiding singularities is a major task while planning paths in the workspace of a parallel manipulator. Various approaches have been resorted to to accomplish this task. For example, Bohigas et al. (2013)[2] numerically identifies the path between two non-singular configurations in the workspace of a parallel manipulator, while the same is achieved by Dash et al. (2005)[4] by identifying and grouping clusters of singularity points and modeling them as obstacles. Another approach as mentioned by Leguay-Durand and Reboulet (1997)[5] is used by to avoid singularities on a path, in a lower dimensional space than the degree-of-freedom of the manipulator, by using the freed degree-of-freedomto avoid singularities. The main limitation of these approaches is that the solutions obtained are specific to the path under consideration and have to be recomputed afresh for every new path, causing a severe computational overhead in real-time applications.

Another approach to handle the problem is to identify singularity-free zones in the workspace of a manipulator and plan paths inside these zones, which would guarantee them being singularity-free. Li et al. (2006)[6] and Gosselin (2009)[7] apply constrained optimization to identify maximal singularity-free zones centered around a given point in the workspace of 3-RPR manipulator and Stewart-Gough Platform, respectively. The limitation of these methods is that they use closed-form expressions for the singularities which are not yet found for all types of parallel manipulators and they also do not take into account all the other relevant issues, i.e., link interference and joint limits, that arise in the workspace of a parallel manipulator along with the kinematic singularities.

Karnam et al. (2016)[8] attempts to address all the above mentioned issues but loses out on the continuity aspect of the scanned 3D region. This work attempts to resolve that issue, as well as improve the performance compared to the existing algorithms.

Objectives

Following are the major objectives which were kept in mind while formulating the algorithms presented in the work:

-

Methodology: Scanning the workspace in a manner which is continuous in all three directions.

-

Performance: Eliminating redundant computations and implementing the approach of growing from the inside to improve the running time when compared to the existing algorithms.

-

Code re-usability: Making the implementation generic enough to be used for any two and three degree-of-freedommanipulator.

Safe Working Zone of a parallel manipulator

Introduction

The algorithms presented in this work find regions which are subsets of the workspace of a parallel manipulator satisfying certain conditions. Following are the definitions of two such regions:

Definition 1: The SWZ, \(~\mathcal{W} (\boldsymbol{o})~\) of a parallel manipulator is defined as a subset of the workspace of the manipulator satisfying the following:

-

It is a connected set and contains the given point of interest \(\boldsymbol{o}\)

-

It is contained entirely inside the workspace of the manipulator, i.e., it is free from loss-type singularities

-

It is free from gain-type singularities

-

There is no interference between the links at any point inside \(~\mathcal{W} (\boldsymbol{o})~\)

-

At no point in \(~\mathcal{W} (\boldsymbol{o} )~\) does any joint violate its physical joint limits

This definition for the SWZ is proposed by Srivatsan and Bandyopadhyay (2014)[9] . In addition to the above mentioned definition, the SWZs considered in this work are convex and are hence denoted by \(~\mathcal{W}_c (\boldsymbol{o} )~ \).

Definition 2: The MSoR, \(\mathcal{M}(\boldsymbol{o} )\) for a parallel manipulator is defined as a subset of the workspace of the manipulator satisfying all the points mentioned in Definition 1 and in addition maintains the following:

- It is bounded by the surface of revolution about a given central axis. This surface touches one or more of the boundaries of the region in the workspace, marked by any of the loss-type singularities, gain-type singularities, link interference and joint limits

The requirements 2-5 in the Definition 1 and Definition 2 have a common characteristic: each define a subset of the workspace, which is bounded by the zero level-set of a corresponding boundary function (denoted henceforth by \(S_i\) ). The following define the terminology associated with these boundary functions.

-

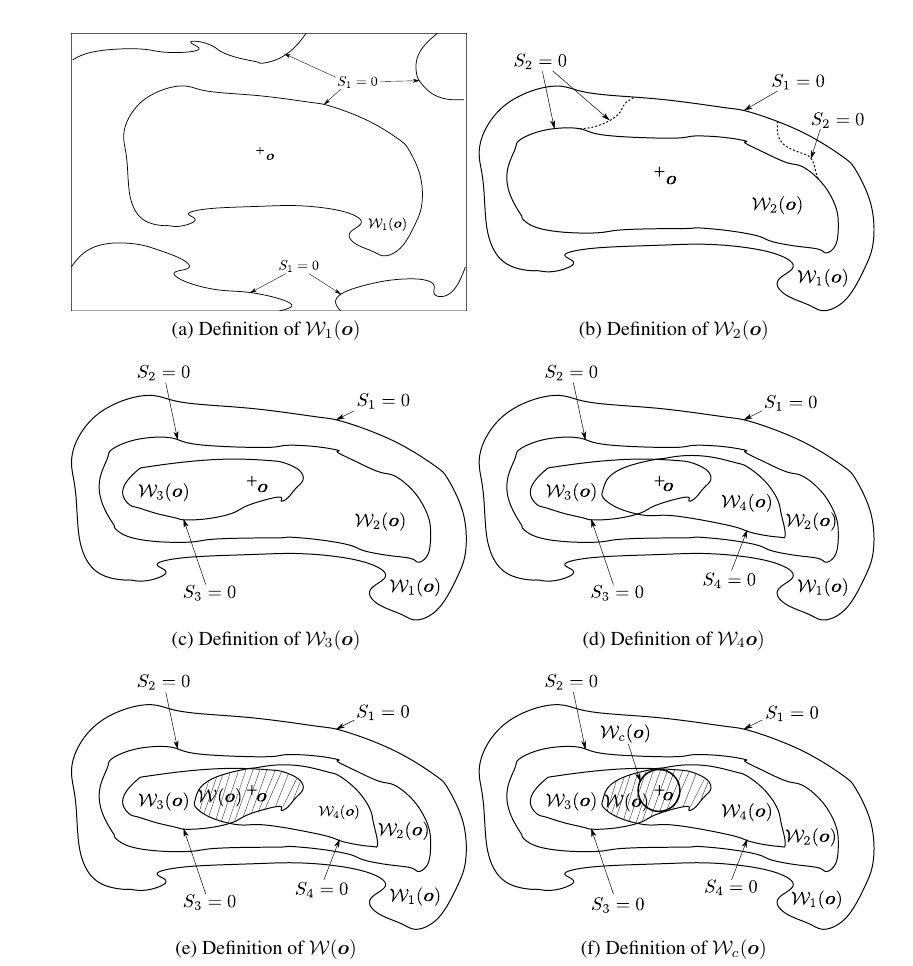

The zero level-set of the condition for loss-type singularity, defined by \(S_1 = 0\), bounds the workspace, as seen in Fig. [fig:w1]. The subset of this workspace which contains \(\boldsymbol{o} \) is denoted by \(\mathcal{W}_1(\boldsymbol{o} )\).

-

The gain-type singularity manifold is obtained by evaluating the condition for gain-type singularity, which is given by the solution set of \(S_2 = 0\). The region \(\mathcal{W}_2 (\boldsymbol{o} )\), which is inside \(\mathcal{W}_1(\boldsymbol{o} )\), and contains \(\boldsymbol{o} \), and is free of gain-type singularities, is bounded by the set of points defining the gain-type singularity manifold, as seen in Fig. [fig:w2].

-

The region inside \(\mathcal{W}_2(\boldsymbol{o} )\) that includes \(\boldsymbol{o} \), and is free of link interference as well, is denoted by \(\mathcal{W}_3(\boldsymbol{o} )\) , and is bounded by the set satisfying \(S_3 = 0\), as seen in Fig. [fig:w3].

-

The solution set of \(S_4= 0\) which falls inside the region \(\mathcal{W}_2(\boldsymbol{o} )\), delimits \(\mathcal{W}_4(\boldsymbol{o} )\), i.e., the space containing \(\boldsymbol{o} \) and free of joint-limit violations (see Fig. [fig:w4]).

As seen in Figure 1e, the SWZ of the manipulator can be found as \(\mathcal{W}(\boldsymbol{o})= \bigcap_{ i=1}^4 \mathcal{W}_i(\boldsymbol{o}) \) .

The detailed report gives an outline of mathematics and general procedure for finding the singularity functions \(~S_1,~S_2,~S_3,~\) and \(~S_4~\) which describe the singularity manifolds of loss-type and gain-type and regions of link interference and joint limit violation respectively. It then goes on to present the algorithms to find the SWZ and MSoR as defined above, the efficiency of these algorithms when applied to a 3-RRS parallel manipulator.

References

[1] Kilaru, J., M. K. Karnam, S. Agarwal, and S. Bandyopadhyay, Optimal design of parallel manipulators based on their dynamic performance. In The 14th IFToMM World Congress. 2015.

[2] Bohigas, O., M. E. Henderson, L. Ros, M. Manubens, and J. M. Porta (2013). Planning singularity-free paths on closed-chain manipulators. IEEE Transactions on Robotics, 29(4), 888898. ISSN 1552-3098.

[3] Gosselin, C. and J. Angeles (1990). Singularity analysis of closed-loop kinematic chains. IEEE Transactions on Robotics and Automation, 6, 281–290.

[4] Dash, A. K., I.-M. Chen, S. H. Yeo, and G. Yang (2005). Workspace generation and planning singularity-free path for parallel manipulators. Mechanism and Machine Theory, 40(7), 776 – 805. ISSN 0094-114X.

[5] Leguay-Durand, S. and C. Reboulet (1997). Optimal design of a redundant spherical parallel manipulator. Robotica, 15, 399–405. ISSN 1469-8668.

[6] Li, H., C. M. Gosselin, and M. J. Richard (2006). Determination of maximal singularity-free zones in the workspace of planar three-degree-of-freedom parallel mech- anisms. Mechanism and Machine Theory, 41(10), 1157 – 1167. ISSN 0094-114X.

[7] Jiang, Q. and C. M. Gosselin (2009). Determination of the maximal singularity-free orientation workspace for the Gough-Stewart platform. Mechanism and Machine Theory, 44(6), 1281–1293. ISSN 0094-114X.

[8] Karnam, M., R. A. Srivatsan, and S. Bandyopadhyay (2016). Computation of the safe working zone of a parallel manipulator. Under preparation.

[9] Srivatsan, R. A. and S. Bandyopadhyay, Computational Kinematics: Proceedings of the 6th International Workshop on Computational Kinematics (CK2013), chapter Determination of the Safe Working Zone of a Parallel Manipulator. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2014. ISBN 978-94-007-7214-4, 201–208.

[10] Patel D., Kalla R., Tetik H., Kiper G., Bandyopadhyay S. (2017) Computing the Safe Working Zone of a 3-RRS Parallel Manipulator. In: Wenger P., Flores P. (eds) New Trends in Mechanism and Machine Science. Mechanisms and Machine Science, vol 43. Springer, Cham